Dad's Mysterious Blindess and A Dry Climate

My father’s mother had died when he was sixteen with the wish on her lips that he get an education. He’d quit school at age eleven to go to work as a runner in Wall Street. His lone sister, Minnie, had to leave school at the tender age of thirteen and take care of the house, cooking and cleaning for a father and four brothers.

In 1901, when he was sixteen years old, Dad started evening school. While he worked days, he took night courses in bookkeeping and Spencerian penmanship. His hand-written letters were things of beauty, but the way he could write a line of numbers across an unlined page was truly amazing for its evenness. By the time he’d reached twenty-five, he was head bookkeeper at a top Wall Street brokerage house, Bache & Co., where fourteen years before he’d started as a messenger boy.

Shortly after the first World War, he went into the brokerage business with a man named Gilligan. They, along with brokers from other firms, traded stocks outdoors year round, stamping their feet on the sidewalk in the coldest weather to keep some feeling in them. This stock exchange was naturally called "The Curb." Some years later, after WWII, the Curb bought a building, moved indoors, and, changed its name to the American Stock Exchange (AMEX), but by then Dad had been out of Wall Street for some time.

In 1928, he began to get an uneasy feeling about the stock market and decided to get out. His youngest brother, Walter, had opened a hat factory that made red buckram firemen hats for kids. These sold in Woolworth’s Five & Ten Cent stores for a nickel. My father joined Walter and ran the office with the help of a bookkeeper/secretary. Walter managed the factory, a four-story building at 2 Bond Street, of which they rented the bottom two floors.

The hats were sort of cute.

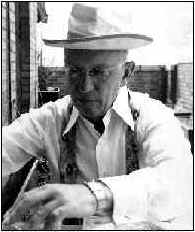

My Dad, Harry Jacobson, eating breakfast on terrace in apartment on West 16th Street.One afternoon, the doorbell of our apartment rang and, when Nellie answered it, two men wearing white brought my father in on a stretcher. As they passed me, standing in the living room, my father gave me a smile. He was forty-three and he’d had a mild stroke. In those days they didn’t take you to a hospital unless you were really injured and dying, or having a baby.

My mother, God bless her, had an inborn equanimity in a crisis. When she arrived home and was told the news, she telephoned our family doctor (who had already been to see my Dad), got the report, and went to work nursing him back to health. Fortunately, he seemed to suffer no lasting mental or physical impairment. But several months later, he started to go blind in his left eye. He’d be fine one minute, and then the next, whammo, no sight in that eye. The condition would last for upwards of a week. Then, the sight would return.

Our family physician, Dr. Friedman, a kindly, gray-haired man, who had brought me into the world, sent my father from one eye specialist to the other. No one could find an answer. Finally, it was decided that he take six months off from work and travel to a dry climate. In those days, doctors decreed "a dry climate" if they couldn’t find any other answers.

We couldn’t afford to keep Nellie. I was not yet six years old at the time, and I remember that our parting was tearful on both sides, for her as well as for me. I felt I was losing a second mother. Most of us are lucky to have one mother who cares for us, kisses our scrapes, and picks us up when we fall. I had two, and it was heart wrenching for me as Nellie kneeled to give me a last big hug.

I spent my sixth birthday in Phoenix, Arizona where two important events occurred: 1) I got my first job, and 2) my father got an answer for his recurring blindness.

We rented an apartment on the second floor of a duplex, just a few streets away from downtown and its biggest and grandest hotel. A young man stood near the hotel entrance hawking the Evening Gazette. (I guess I considered him a man, though on reflection he was just a teenager.) Before long, I was standing there with him, helping with his brisk business. A few days later, an older man (I could tell, because this one had a mustache) who delivered bundles of the paper to my confrere, asked if I’d like to have a paper route of my own.

Twenty minutes later, my parents, who were taking some air on the front porch, saw me approaching, barefooted, in a one-piece bathing suit (after all, it gets to 116° in the shade during summer), with a bundle of newspapers under one arm. In my child’s alto voice I cried out, as I’d picked up from my former partner, "Evening Gazette, payyyyyy-pur. One cent!" I made my first sale to a nice looking, grinning, couple (my parents) who gave me a penny and told me not to be late for dinner.

Mom and Dad played bridge many evenings with a nice couple who were permanent residents and had an apartment near ours. One evening during the game, Dad’s left eye went blind. He put his hand up to it, and this led to the long story about the stroke. When he’d finished, the couple insisted he see their doctor, a family physician, but my father remonstrated, saying that a general practitioner could hardly do what a whole series of eye specialists had failed to. But, at two dollars for an office visit, he was talked into it.

This doctor asked my father a lot of questions and examined him thoroughly. "Mr. Jacobson," he said "have your tonsils out, they’re extremely enlarged." When we returned home to New York, that’s just what he did, and he never had an eyesight problem again.