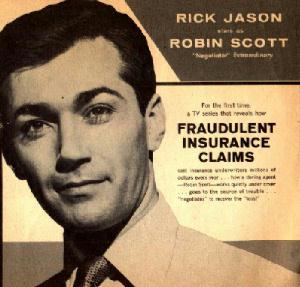

Another Loss for Gene Barry:

How I Got My Hollywood Stand-In Jack Jackson

About five weeks

into the show [The Case of the Dangerous Robin], I

walked on the set one morning after wardrobe and makeup, and Don Verk came over to me with

a man, maybe late fifties or early sixties, a few inches shorter than I. "This is

Jack Jackson. He’s going to be your stand-in." Just as he started away, Don

added, "He works for Gene Barry, but Barry’s…"

About five weeks

into the show [The Case of the Dangerous Robin], I

walked on the set one morning after wardrobe and makeup, and Don Verk came over to me with

a man, maybe late fifties or early sixties, a few inches shorter than I. "This is

Jack Jackson. He’s going to be your stand-in." Just as he started away, Don

added, "He works for Gene Barry, but Barry’s…"

"…doing rodeos this week," I finished for him.

Jack and I shook hands and he reached for my script, took it out of my hands, went over to my canvas chair and put it in the pocket.

I’d never had my own stand-in. An extra who was about my height would be selected and I doubt that I ever had an opportunity to even talk with one before. He’d step out just before I stepped in for final lighting, and that was it. Each day it was someone else.

Jack came back with a cup of coffee. "You take it with cream and sugar," he said. "Two lumps."

I looked at him. "How did you…?

"Can I do anything else for you, Mr. Jason?" he asked

"Yes," I said, "one thing you can do, Jack, is start addressing me by my first name."

"Sure thing," he said and smiled broadly. He had about ten teeth in his mouth, with big gaps between what was left of them.

Since I was in almost ninety per cent of all the footage we shot, I had about five to seven wardrobe changes a day. That, plus blocking every scene with the director and the other actors. Along with individual close-ups to cover every scene, which we shot after all the other actors had been dismissed, I was always in for a sixteen- or seventeen-hour day. Later, I’d drop into the editing room and stand over somebody’s shoulder, learning how to do what they did.

I’d ask why they were using a close-up of me when it should be the other actor or actress. "You stay with the money," was the standard answer.

"But wouldn’t it make it better for the scene?" I’d ask. I finally got the editor to start looking at footage from a slightly different point of view. It was opposed to the way he’d been trained, but he was good, and he could see what I meant. He just had never thought about it in any other way. The shows began to look better, too. It was quite ego-fulfilling to see my fizz on the screen so much, but it didn’t necessarily make for a better show.

The second day after Jack Jackson came to work I walked onto the set, after having changed wardrobe for a new scene, and he stepped out of the set, handed me my script and said, "We’ve roughed it out and I’ll show you the director’s blocking." He went through the whole thing in about thirty seconds. I stepped in and we made a few minor changes in moves, rehearsed once or twice until we were comfortable with it, then shot it.

By late Wednesday afternoon, I saw that I was going to finish almost two hours early. I slumped in my chair, conserving what adrenaline I had left for the rest of the day’s work. There was a light tap on my shoulder, and as I turned part way around, Jack handed me a cup of tea. There was honey in it. "Thanks, Jack. Where’d you get the honey?"

"Brought it from home," he said.

"Let me pay you ba—," but he was gone.

Jack was saving me all that time and energy, walking through the rough scene blocking with the director, while I changed clothes. He was always there when I wanted a cup of coffee or tea. How he knew I was about to get up and go to the coffee wagon I’ll never know.

Friday evening, as we shot the last scene of the week, Jack, as usual, was standing just off camera, watching, holding my script in its leather binder. As he handed it to me I thanked him for a great week, and said how much I was going to miss him.

He elected to stay.

Over the years, I tried to get Jack to have his teeth fixed. I offered to pay for them and made an appointment at my dentist. He never showed up.

He’d worked for Barry Sullivan when Barry was a star at MGM and later was his dresser on Broadway when Barry was doing The Caine Mutiny. Barry and I knew each other, and in comparing notes on Jack, he told me he’d had the same problem, and in the same way, "He never showed up at my dentist, either," he said. Sullivan had done a series at Ziv that only went one year, but that’s how Jack got introduced onto the lot.

Stand-In Interviews at MGM Studios

Jack started out as a chorus boy in MGM musicals in 1934. In those days, extras supplied their own tuxedos and tails. You could buy a custom made set of tails — white vest, wing collar and white bow tie — for seventy dollars. With those accoutrements you were known as a dress extra and could earn an additional seven-fifty a day.

Dance directors got used to working with the same chorus boys and girls, and requested those who understood what they wanted. Eventually MGM had its own stock company of chorus boys and chorus girls under contract. By the time Jack had been working at MGM for almost fifteen years, he was getting a little tired in the legs. Days of eight- to ten-hour rehearsals, to shoot an intricate dance number, with all its various camera angles, and cuts, took its toll.

The major studios took care of their own, so Jack was interviewed to be a permanent stand-in for Louis Calhern. (I could hardly believe it when he told me he was actually interviewed to be a stand-in!) Louis Calhern was one of MGM’s leading contract character actors. When Calhern wasn’t making a picture, Jack was assigned as stand-in for Walter Pidgeon, also an MGM contractee.

Once Pidgeon and Calhern were doing pictures at the same time, and there was a terrible fight as to who was going to get Jack. Louis B. Mayer had to come down to the sound stages and settle the matter personally.

And now I had Jack.

He spoiled me rotten. Would never let me carry anything back to my dressing room suite at night when we finished. "Give me the suit, Jack, you’re carrying three of them. I’ll take the shirts, too—’

"Never mind. Just go on. You’re a star! Stars aren’t supposed to carry things."

"Bullshit! I’m a lucky actor doing leads. Gimme the goddam suit."

"No! And that’s final. Besides, from now on I’ll tell wardrobe to pick up your clothes from the box trailer on the set." Suits and shirts were picked up every night by the wardrobe department, sent out to be cleaned, pressed, and were back in the morning.

There was something Gene Barry had that Jack was convinced I needed. Instead of a low-slung canvas director’s chair, Gene had a high cinematographer’s chair with leather seat, his name hand tooled into the rear of the seat back.

I walked on our set one morning and couldn’t find my canvas chair. "Where’s my chair?" I asked. One of the guys in the crew pointed haphazardly to a cinematographer’s chair with a tooled leather seat and back. I went over to it, coffee mug in hand and looked at it as if it was something that belonged in a zoo.

All activity on the set had ceased. There was no hammering, nobody calling for a "single" or a "plug me in." The entire company had stopped and was gazing at me. I glanced at all of them as I walked around the chair and saw, "Rick Jason" tooled into the backrest. They were still watching my reaction.

"You guys have got to be kidding!" I said, "I’m not going to sit in this…this…throne!" Jack walked up to me and placed my script in one of the large tooled-leather pouches hanging from each armrest like saddle bags.

"Sit down!" he commanded. "I bought the chair, the entire crew chipped in for the seat and back, and our prop man had it made and he installed it. So shut up!"

I was open-mouthed. I sat "up" into the chair and there was general applause and shouts and whistles from all present. I was so touched and humbled I didn’t know what to say. It was just as well. A moment later, Don Verk’s voice rang out, "Al-l-l-l-l-l right! We have twelve-and-a-half pages to shoot today, so let’s get moving!"