The Psychic and the Hat Factory:

Making Texaco Fire Chief Hats for the Ed Wynn Show

Aunt Carolyn was a great believer in the occult. During each visit she made to New York, she’d get a psychic reading from Mrs. Tavorazzi. Mom went with her once, and, not being a great believer in that sort of thing, waited in the sitting room. She didn’t wish to spend the hard-to-come-by two dollars that a reading cost.

Most things of any importance cost two dollars in those days.

Mrs. Tavorazzi, who never wished to know anything about her clients that she could not foresee herself, emerged from her "reading" room. She said to my mother, "There is a ‘J’ around your name."

My mother, a little startled, began to say what her name was, but Mrs. Tavorazzi held up her hand. "And how is the baby?" she continued.

"Baby?" my mother asked, completely confused. "I don’t have a baby. My little boy is almost seven years old."

"Well, you treat him like a baby," said the tall, distinguished lady, and she ushered my aunt into the other room. Of course, it was quite true, I was still being treated as a baby.

The Hat Factory in the Depression

Years later, in recounting the early days of the Depression, my father would say he felt he was stealing his salary from the failing hat factory. The forty-five dollars a week fed his family and paid the rent, but the business could barely afford it. Each week it was a struggle to meet the payroll. Dad used to put his feet on the floor in the mornings and ask himself, "How do I get my hands on a hundred dollars?"

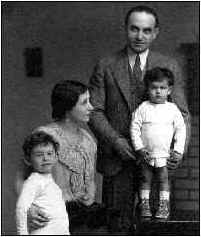

Aunt Carolyn and "Unk" Lou Becovitz with their two adopted boys.Carolyn and her husband Lou had a ladies shop called the Vogue, which was, for its time, the Bergdorf Goodman of Bloomington, Indiana. Twice a year, Carolyn came to New York on a two-week buying trip in the garment district and spent many an evening over dinner at our apartment. My mother would accompany her sister from showroom to showroom, and filled out her wardrobe at wholesale prices. Having a father as a furrier, when my parents could afford to go out for an evening no one suspected from the way they dressed that they were close to being broke.

By early spring 1931, Jacobson Company was on its last legs. The only customer they had left was Woolworth’s, and that was hardly making a living for them. One evening over dinner, Dad mentioned to Carolyn that he and Walter were considering closing the factory.

"What will you do?" Carolyn asked.

"I don’t know," he said, "maybe go back into Wall Street."

"Harry," my aunt pleaded, "that’d be worse than where you are now. You know better than anyone what a mess Wall Street is in these days."

"I don’t know what else to do," he said.

"Before you make a final decision, go and see Mrs. Tavorazzi."

"Carolyn, you know I don’t believe in that nonsense," my father rejoined.

"Call it nonsense if you like, but just the same, it certainly can’t do you any harm. I’ll even pay the two dollars."

That got to my father’s pride. "All right," he said, "I’ll go see Mrs. what’sername." Carolyn wrote the name, address, and phone number down. Several days later, the piece of paper must have been burning a hole in his pocket because, out of the blue, he stepped into a pay phone and called the lady.

When he entered her apartment on West 73rd Street, Mrs. Tavorazzi ushered him into a dimly lit room, decorated only by a huge oriental carpet and two upholstered, carved wooden armchairs facing each other. She directed him to sit in one and asked if she might hold something of his, such as a ring or a personal item that he’d owned for awhile. He took out his pocket watch and fob and handed it over. She rubbed it for a time between her palms, then said, "You are in business with your brother." Dad started to say something, but she held up her hand. He settled back.

Mrs. Tavorazzi spoke with a decided Hungarian accent. "You two don’t get along well. You argue all the time," she said.

Somewhat surprised my father started to say, "That’s ri—"

Again she held up her hand. "Please!" she demanded. "You have been thinking of closing the business. You must not do so!"

"But we’re hardly making a living," Dad said.

"It doesn’t matter. You must put such a decision off for at least six months," she said.

"Six months?" he asked.

"At least six months. I see before me … this is a little confusing … millions!"

"Millions?" my father asked, "millions of what?"

"I don’t know. All I see is millions."

"Millions of dollars? Millions of hats? What?" the new convert asked.

"I don’t know," she said and handed him back his watch. "I can see no more."

That evening when Dad got home, he was in a complete state of confusion. He repeated to my mother exactly what had happened. Then they were both confused. For want of anything else to do, my father, being too embarrassed to tell his brother about the psychic, convinced Walter that it wouldn’t hurt to stay open another six months. About six months later, a man walked into the office and asked my father, "Is this Jacobson Company?"

The name was emblazoned in raised gold letters on the window behind Dad’s desk. He pointed with his thumb over his shoulder and answered, "That’s what it says. What can I do for you?"

"For one thing, I’d like to tell you it’s taken us almost six months to find you."

"That’s strange, we’re in the phone book."

"The problem is that Woolworth’s will not give out the names of their suppliers. We had to hire a private detective agency to locate you. I want to place an order," said the man.

Dad invited him to have a seat in the wooden armchair next to his desk. The man’s business card had on it the name of an advertising agency — a complete world away from anything my father was accustomed to.

"This is a rather unusual order," the man continued.

"All right."

'Fire Chief' Fireman Hats for Texaco

Comedian Ed Wynn

in costume backstage for

Hooray for What!

18 in. x 24 in.

"Our firm represents the Texas Oil Company, you know, the makers of Texaco gasoline."

Dad said, "I don’t own a car." But the man pushed on.

"Texas Oil is going to sponsor a half-hour comedy radio show beginning in September, that’s only eight weeks away. They’ve chosen an established vaudeville comic named Ed Wynn, and they’re going to advertise him as the "Fire Chief," which is what Texas Oil is calling their new gasoline. They want to give away a hat to each customer who purchases five gallons of their gasoline. Ten gallons, two hats."

"All right," said Dad, still not picking up what might be in store. "What may I do for you?" he said, quite innocently.

"We’d like to place an initial order for 600,000 of your firemen hats."

Without giving himself a moment to digest this piece of news, Dad said, "All right."

"But there’s a hitch," said the man.

"Oh?"

"It’s taken so long to find you, that we don’t have that much time left. You’ll have to drop ship to Texaco stations all over the United States, can you do that?" he asked.

"I see no problem," Dad answered.

"And everything has to be in place in six weeks."

My father nodded. He’d been in Wall Street too long to get shaken up easily. "You mean shipped out in six weeks?" he asked.

"Yes. It will take about a week to ten days at the most to get all the boxes to stations around the country, which is about one week before we go on the air. Also…" he started to say.

"Yes?"

"The shields must say, "Texaco, Fire Chief." He handed Dad a drawing of the existing shield, with the new wording, logo, and its placement. "Can you do it?" he asked anxiously.

"I don’t see any problem," Dad said, and although he never afterward admitted to anything, his heart had to be racing. The man left after stating a work order would be delivered the following day, with an advance payment of thirty percent. Dad and Walter made a deal with the building owner, who was only too glad to rent the top two floors of his half-vacant building. He gave the two brothers an option to buy the place at a price that pleased them all. In the Depression, he would have been happy to get it off his hands. Later on, Dad and Walter purchased it.

They moved a cot into the office, bought another dozen used hat dies, some used cutting machines, stapling machines, and hundreds of cartons. The factory hands trained new hirees to make the buckram firemen hats. Practically all of them were family members, brothers, sisters, cousins, all out of jobs for more than a year. They were all Eastern European Jews and Italians who all got along famously with each other.

Making Toy Hats from Buckram

DVDs with Ed Wynn:

Buckram is a heavily starched, loosely woven cotton fabric. It came in huge rolls. At the factory, the workers cut it into to squares about twenty by twenty inches, then stacked and dampened. Dad’s factory had a long row of iron presses, each containing a male die at the bottom, secured to a steel base by bolts under which was a gas burner. A female mold was above it, which could be lowered and locked into place by a foot pedal. With a man on each side, one man would reach behind him for a piece of buckram, which he’d toss over the male press to his fellow worker on the other side. They’d each pull at the corners while the man on the other side pressed down on a pedal, bringing down the female portion of the die and locking it in place, they’d then move on to the next press. When they finished the row, they’d walk back to the first press, release the foot lock, and the first man would remove the blocked pressed hat, reach for another piece of buckram and away they’d go again. After that, the hats were sent for trimming in an adjoining part of the factory. Trimming was done four hats thick, in cutting blades worked by a foot switch on a machine that resembled an electric sewing machine. Then the hats were sent upstairs, where cardboard shields were set in place with two big chromed staples. From there, the finished hats went a few feet away to the shipping department.

My Dad and Walter set up three eight-hour factory shifts, seven days a week. Dad and Walter each spent a twelve-hour shift at the factory, catching a nap on the cot when they could. Shipments of raw materials arrived at all hours of the day and night. All four floors hummed like a beehive. In six weeks, they started shipping. Everything arrived on time and in place.

The Ed Wynn show became the biggest hit yet to be on radio, where it remained for a number of years. Before they were done, Jacobson Company sold over ten million buckram firemen hats to the Texas Oil Company.

Thank you, Mrs. Tavorazzi, wherever you are.