The Value of Money

and

Grandpa Buys Me a Pet Turtle

Probably the most dramatic event of my childhood occurred the first winter we lived across from the armory. It had snowed and the streets were wonderfully icy. Since we lived on a hill, we kids took turns hunching down on our heels and having someone push from behind. I’d push my friend Reese Patterson, then he’d push me. With a good start you could slide about fifteen feet.

On one push, however, I lost my balance. My forehead, just above my left eyebrow, stopped my movement by way of one of the iron bars on the armory window. Reese was scared to death and walked me across the street and up the one floor to our apartment, 2C. Mother answered the door and immediately called father when she saw the flow of blood down my cheek. I was dutifully marched into the bathroom where Dad reached into the medicine cabinet for some cotton and peroxide. When he dabbed away the blood, he exposed a white line, which was my skull — after all, a kid’s skin is pretty tight. My mother standing behind me fainted dead away.

Dad told me to stay there and hold the cotton on my wound while he carried Mom to bed. Then he called Dr. Friedman, who showed up in almost no time. I sat on my father’s lap on a chair at the kitchen table while the good doctor intoned that I’d need about three stitches. Dad said he’d give me a nickel if I didn’t cry.

Money has never meant very much to me, but a nickel was a nickel! You could buy five pieces of penny candy or an extra bag of popcorn at the Saturday afternoon movie. I may have made a few grunted "hmms," but I earned the nickel.

Up the street and around the corner on Broadway was the Uptown theater, a neighborhood movie house that was filled completely by kids at Saturday matinees. Each Saturday my mother gave me fifteen cents. Then I and my best friend Reese, also with his fifteen cents, would head for the Uptown. If we went in before one o’clock, admission was ten cents; after that, it was fifteen cents. We always got in just before one and that left a nickel for popcorn.

We would see two features, news, a cartoon, and there was a break at about three in the afternoon between the first and second features. The theater manager would come on stage in his tuxedo while two ushers pushed a large wheeled table loaded with toys and games. Another usher pushed a round cage out from the opposite wing. They’d roll the cage on its axis a few times; then the manager would unlatch a door in the middle and swing it open on its hinges. A young member of the audience (who had been chosen at random to come on stage) would pick out a torn ticket stub. We’d all examine our stub halves as the number was read and if your number was called, you ran up on stage and were handed a prize. This went on until the table was bare, then, on with the movie. I won my fair share of prizes, such as a bow and arrows with rubber suction cups on their tips.

The Uptown on Saturday evening about seven o’clock is where my father could always find me and take me home to dinner. I have a feeling that a lot of fathers ran into each other in that lobby toward mealtime on Saturdays. My Dad got so he could walk into the dark theater and just about sniff me out. But I got to see the movie about two and a half times.

After seeing Tarzan the Ape Man with Johnny Weissmuller and watching Rin Tin Tin, the smartest German shepherd in the world, I decided what I was going to do when I grew up.

I began elementary school the year we moved to 169th Street. That year I watched construction begin on the George Washington Bridge linking Manhattan with New Jersey, which eliminated the ferry service. I read recently that ferry service is about to be re-installed to relieve the traffic congestion on the bridge. I’m not quite sure if that’s progress or serendipity.

Grandma and Grandpa then lived in a ground floor apartment on my old street, 172nd. One of their great joys, and mine, was the weekends. Saturday mornings I would ride the subway with my father to the hat factory, where I could play all morning. I was spoiled there by everyone: Johnny de Gaetano (a trimmer who later became factory foreman), Mary (who worked right next to him and soon became his wife), and all the other employees, mostly Italian and Eastern European Jews who kidded around with me and showed me how the hats were made.

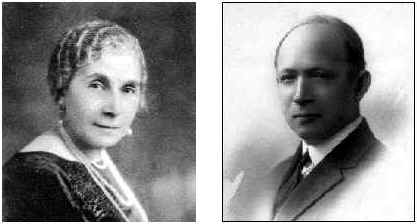

Grandma and Grandpa Wohlfeld in the 1920s.

Every few Saturdays before noon, Dad would drop me off at Grandpa’s fur factory, about a mile away. I’d always have fifteen minutes or so to examine the factory while Grandpa’s employees shut down their machines for the Saturday afternoon and Sunday weekend. The first thing Grandpa would ask, as he locked the factory door behind us, was, "Where should we have lunch?" He always knew that I’d choose the cart a few streets from his factory, where the man stood under an umbrella at the curb and sold hot dogs with mustard and sauerkraut for a nickel, and gave a free glass of lemonade with each dog.

After lunch, we’d stroll hand-in-hand to the nearest movie house where we could always be sure of seeing a great cowboy picture with Hoot Gibson or Tom Mix or Harry Carey or any of the other great Western stars. It was always a double bill: two pictures, a newsreel, a short subject and a cartoon. We’d stay and see the show twice, a total of about five hours. As I look back, I wonder if he wasn’t a bigger kid than I was.

We’d take the subway home, where Grandma had a good meal waiting. Grandpa could never eat dinner without benefit of beer, and he kept a goodly number of bottles in a bedroom closet. This was the prohibition era, so he got his supply from a bootlegger, just as everyone else did. The beer was kept cold in the ice box. To keep it chilled, every other day the iceman brought in a good size block of ice for twenty-five cents. In the dining room credenza, Grandpa kept a bottle of schnapps and a shot glass. Before sitting down, and after we’d washed our hands, he’d pour half a shot glass of the liquor and toss it down. It was then time to eat.

On these Saturday nights, he’d pour his beer into his favorite stein and then fill a small juice glass of dark foamy bock for me. We’d clink glasses, and then say in unison, "Hock der Kaiser, wolzein, drink ‘em down! AAhhhhhhhh." I never knew what it meant but that didn’t matter.

Although we were Jewish, it meant nothing to me, even less to Grandpa. He was a self-styled atheist and had raised his five children that way. His reasoning was that if there were no religious differences among men, most all of the wars would have been averted. And if there was a God, what kind of God would permit brother to slay brother in the name of a different way of worship? My father and his brothers and sister had had no religious training to speak of, so as I grew up, I knew I was Jewish but it didn’t have a deep impact on me. I think some friends of mine, and of my parents, went to temple, particularly on the high holy days, but I never set foot, except once, inside a synagogue until I was well into my teens. You can’t miss what you’ve never had.

The Depression had not made the least impression on me. It was only later, when I was old enough to understand, did I learn what my folks had gone through. More than a quarter of the national work force were without jobs, and there was no such thing as unemployment insurance. Up, down, and across the entire nation, along the railroad tracks, "hobo camps" grew up out of nothing. Men hopped freight trains from town to town, looking for work. Most of America was agrarian, so the best a hobo could hope for was maybe chopping some wood for the stove or doing menial farm chores, and having a good meal to follow.

I would play near the palisades a few streets away from our apartment. Looking down a hundred or so feet to the shore of the Hudson, I saw all up and down the river homeless men living in shanty shacks made of empty wooden crates or huge cut-up tin cans. I used to walk down there. I remember meeting nice men of all ages. They knew by the way I was dressed where I came from. But if they were having a communal stew made of whatever they’d all collected, they never hesitated to invite me to participate. I got in the habit of helping myself from our pantry and delivering dozens of cans of food to my new-found friends. My mother either never noticed, or, if she did, never said anything. She’d go shopping and the larder was always full.

I can remember getting only one spanking in all my childhood. I was probably seven years old and was forbidden to cross the street without the hand of an adult. What I’d do was go around the corner, then cross. In the spring days, when the weather was gentle, I’d come home from school, get a baking potato, rush down the stairs, outside, around the corner, across the street and run the short block to the palisades where I’d meet several buddies, each of whom had a potato. We’d build a little fire and, when it had burned down to coals, we’d toss the potatoes on the red embers, turning them occasionally for about fifteen minutes until they were black. Then we’d stab them with long green sticks and sit there, eating a great afternoon snack. This joyful, half-cooked delight, was called a mickey, probably because potatoes were associated with the Irish. The charcoal rubbed off on our hands and faces, but at our age who cared, they were delicious! Even the raw part.

Unfortunately, one day I when I rushed to get to the potato bake I forgot to go around the corner and a neighbor saw me cross the street. By the time night fell and my father was home from work, I hadn’t shown up. My parents asked around and found out about my indiscretion. By the time I walked through the door, they were calling the hospitals and police.

My mother ran to me, crying, and begging to know where I’d been. When my father asked if I’d crossed Wadsworth Avenue against their direct instructions, I shook my head.

It was definitely not the right answer.

I was picked up and tossed on my stomach on the sofa. My father reached into the hall closet for a thin hanger, just a slight wooden arc with a wire hook sticking out from the center. After three or four blows on my rear end, the thing broke. My father, more exhausted by the nerve-racking experience than the exercise, collapsed into a chair, wiping the sweat from his bald head with a handkerchief. I lay there and screamed, more from fright than hurt.

I never did it again — until I was old enough to cross the street without permission. Years later, I laughingly recalled the incident to Dad. He had absolutely no memory of it. But he did remember another time with Grandpa.

I was nine. Grandpa picked me up at home in the afternoon for a movie that we both wanted to see, and we headed out to the "movie palace." Loew’s 175th Street: a demeaning name for an extravaganza of a lobby with a thirty-foot ceiling, gold-leafed gilded plaster angels floating high against the walls, and beautiful carpet that made me think I was sinking up to my ankles as I trod across it. We saw King Kong starring Bruce Cabot and Fay Wray, with whom I immediately fell (and ever since have been) in love. After the first show I said, "Grandpa, can we see it again?"

"Sure. I’ll get some more popcorn."

We stayed for a third show. On the way home from the theater, we stopped in at a pet store to get me a green-backed turtle in a shallow bowl, along with some gravel, a small stone, and some turtle food.

By the time we arrived back at Grandma’s, my parents were there. It was after eight in the evening and all three of them came at the poor man as if he were a kidnapper. I sat out of the way on the couch, holding my latest possession in my lap.

After ten minutes of their screaming at the tops of their voices, I cut in with my shrill, little voice. "Why is everybody mad at Grandpa? Look! He bought me a turtle." Three furious adults turned to me as I proudly held up my acquisition.

Somehow, that put an end to it.